I’m all about making money for subscribers.

I don’t spend a lot of time mulling over macro stuff. I want to know the macro basics and then research and discover which companies will profit.

There are a lot of guys MUCH smarter than me when it comes to figuring out where the Market is going, or even where one small industry is going.

And sticking to that thesis made my first-ever LNG (Liquid Natural Gas) Conference in Vancouver on Wednesday a huge success. Sponsorship by Wolverton Securities allowed me to bring in two Tier 1 experts explain Canada’s place in the LNG world to the 250 attendees (who gave up a rare sunny day in Vancouver to listen!).

And then the audience heard from seven small and mid-cap public companies that will benefit greatly from the $100 billion dollar infrastructure build that LNG should give western Canada. That’s how you make the money.

Here’s my take on the Key Points of the Day from the speakers, and some of the Key Points from the CEOs of the public companies.

I was the first speaker—but only for a few minutes. My main message was that the energy services companies—the drillers, the frackers, or pumpers as they’re called—and all the construction companies who do the dirty grunt work preparing drill sites and pipeline right of ways etc.—all these stocks had a good summer run and are now stalling, waiting for the next catalyst in the LNG game.

I told the crowd I think that’s happening in October, when Golar (GLNG-NASD) and the Haisla First Nation likely announce a Final Investment Decision (FID) on their 0.2 bcf/d export project in Kitimat. This will either be the first or second small scale LNG export facility in the world—this is brand new technology. I think that news could spur a lot of these stocks up.

Another catalyst—that’s much less clear on timing—is the first announcement of a long term gas contract from one of the larger groups, like Shell or Chevron.

Chris Theal from Kootenay Capital was the next speaker. Chris is a plain talker—you always know where you sit with him. I think that comes from his time in the Canadian military. He is a disciplined investor!

He dispelled the talk that Asia would be able to buy cheap LNG, based on North American natural gas pricing. LNG pricing must and will remain linked to the oil price—about 14-17% of Brent—if anybody is going to build new multi-billion dollar terminals.

Every minute investors worry about cheap LNG for Asia…well, you’re just never going to get that minute back.

His favourite way to invest in the LNG build out is through the services stocks. He likes the drillers with rigs that can drill the deep Duvernay formation in western Canada. And he sees a big pinch in fracking capacity in western Canada next year because of that—giving the frackers a lot of pricing power starting in Q2 2014. He is positioning his Kootenay Capital fund now for that run (www.kootenaycapital.com).

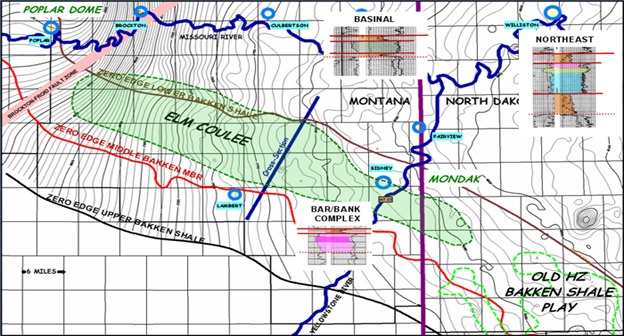

Chris said Canadian gas producers are “in the right basin” when it comes to sending gas to high-value Asian markets. He estimated that all-in costs to deliver gas from most areas of British Columbia should come in below $10/mcf. Very competitive with supply from the U.S. Gulf Coast, where shipping costs for transiting the Panama Canal make landed gas in Asia likely to cost well north of $10/mcf.

He believes that gas from the Montney and Duvernay plays are particularly attractive in terms of supplying cost-effective LNG—especially the Duvernay, where initial production rates from gas wells have been rising, while drilling costs continue to drop as producers learn the rock.

The Horn River play, he said, has trickier economics—but could still be competitive with other sources of gas globally.

Next up was Nathan Weiss, who flew in from Boston to speak to our retail audience. Nathan publishes a very expensive institutional research newsletter called Unit Economics, and only keeps 30 clients; we were VERY lucky he was able to fit us in his schedule.

He is one of the few original thinkers in the market, and one of the rare men who do true, primary research. He doesn’t synthesize what others tell him. He doesn’t need or even want to know what brokerage analysts are saying. He creates his own financial models from scratch, using original data points.

That allows him to get very granular in economic detail. And he did that for us—have a look at this slide on his estimated costs for BC LNG going to Asia. There were about 10 slides that got him to this:

Some other interesting tidbits from Nathan’s presentation: every 1 billion cubic feet per day (bcf/d) of natural gas exported from western Canada should produce 15,000 direct and another 30,000 indirect jobs for the area. There are now proposals for 13 bcf/d. You do the math.

He did warn that the two LNG facilities in Oregon could eat Canada’s lunch—using Canadian gas but only generating upstream Canadian jobs, NOT the high-paying construction jobs for the export terminals themselves—if BC misses its timing window.

We heard from a stellar line-up of public company CEOs who outlined their investment merits to the audience. There was a good mix of presenters:

1. Canada’s two largest fluid services companies (drilling mud)—Secure Energy (SES-TSX) and Canadian Energy Services (CEU-TSX) ;

2. Two leading intermediate natural gas producers in western Canada—Painted Pony Exploration (PPY-TSX) and Bellatrix (BXE-NYSE/TSX)

3. Three construction support companies—Petrowest (PWR-TSXv), Entrec (ENT-TSXv) and Enterprise Group (E-TSX).

Oilfield Services: The Way to Play

Ian Hogg of construction and transport group Petrowest (PRW-TSX) told how one of his firm’s clients in the LNG business believes that costs for a single facility may end up as high as $80 billion.

Petrowest is the largest custom gravel-crushing company in western Canada, among their many services for construction of roads, drill pads, and other facilities. Most of the gas infrastructure that has to be built to supply Canadian LNG is going to be in very remote parts of British Columbia and Alberta. Quick and affordable construction is a must for operators. He showed a slide of all the LNG proposals on the board now and he said they were ALL customers of his.

Des O’Kell of Enterprise Group (E-TSX) had a great video of how their proprietary technology pre-heats new pipelines in the north. I had no idea how important this was. The oil out of the ground is hot and can cause the pipe to crack and leak. Between that division and their tunneling division, they are positioned to be one of the top beneficiaries of LNG development.

Other services groups are trying to anticipate niche industrial needs for LNG developers. Entrec (ENT-TSXv) CFO Jason Vandenberg described how his firm recently purchased the largest crane operator in western Canada. Cranes have the best profit margins I see in the LNG construction game.

Most LNG facilities will be built as modular components, requiring big cranes for construction, shipping, and reassembly at site, not to mention ongoing maintenance. Vandenberg noted that Entrec’s crane operations have been servicing LNG heartland Kitimat for decades—giving the firm a big leg up on would-be competitors here.

Then of course, there’s the actual drilling that’s going be needed to get gas out of the ground. Craig Nieboer, CFO of Canadian Energy Services (CEU-TSX), pointed out that none of the gas projects in the Montney or Horn River plays are yet in “harvest mode.” Producers have been sizing up the plays with exploration drilling—assessing design and spacing of wells to optimally exploit these fields.

As things ramp up toward LNG output, gas companies will need to convert thousands of well locations from conceptual reserves to actual production through the drill bit. Canadian Energy is helping them do that cheaper by designing specialty chemical solutions for drilling muds. This is a space where a 10% increase in drilling efficiency can create hundreds of millions of dollars in savings on a big drilling program. And producers are willing to pay top dollar to services firms like CEU that can deliver those efficiencies.

Secure Energy Services (SES-TSX) VP Nick Wieler also noted that services needs in BC will extend beyond drilling. Secure is looking to help gas producers with waste processing and disposal from drill sites and production facilities. Secure has a big lesson for investors: Their business is not sexy, but this is one of the highest-margin segments of the services business—they have the highest corporate profit margins of any company I know of in the energy services sector.

And like Nieboer’s CEU, their stock is never cheap. But if you let that bother you, you would have missed out on a $3-$15 run in the last three years.

Secure is building out its facilities in northeast British Columbia to be ready when hundreds of wells start spudding en masse.

BC Gas: Great With LNG, Good Without It

The conference’s two presenting E&Ps—Painted Pony Petroleum (PPY-TSXv) and Bellatrix Exploration (BXE-TSX)—were quick to point out that LNG would be icing on the cake for BC gas producers. But by no means a necessity.

Bellatrix CEO Ray Smith’s outlined what has turned his company into a very low cost producer. With over 400 barrels per day of liquids coming out of BXE’s wells in the Notikewin (also known as the Spirit River Formation), gas is almost an after-thought to economics.

Ray is a fantastic public speaker—one of the best I’ve ever seen. He is worth driving to see. One of the attendees quipped that the trading symbol for Bellatrix should be R-A-Y. He explained very clearly that if LNG goes ahead, natural gas prices are going higher and as a low cost producer, his shareholders have the most leverage.

Painted Pony President and CEO Pat Ward has the simplest story—he has massive reserves of natural gas located in B.C., which is what the big LNG companies want. Their ground is right beside Progress Energy, which Malaysia’s Petronas bought for $6 billion. If someone bought Painted Pony on the same metrics, their stock would be over $20. It now trades for $8. And BG Group is openly on the hunt for gas supply.

They are hitting some amazing wells—in the Montney they have hit up to 24.5 million cubic feet per day. The company’s results here to date have set up an incredible drilling inventory of 290 horizontal locations. There’s going to be lots to exploit if and when LNG developers come looking for supply.

Should Investors Bet on Big or Small LNG?

The day ended with a speak-off between our resident analysts, Chris Theal and Nathan Weiss, on the scale in LNG development. Chris is a believer that large mega-projects will win the day, while Nathan’ analysis shows that smaller-scale, floating developments may actually deliver competitive operating costs… at much lower initial capital expenditure.

It’s a very germane debate, as the first LNG export facility in western Canada will be the small scale Golar one. All the other proposals are 20x the size of it. Twenty.

Weiss believes that capacity to gasify and ship BC gas will cost about $30/mcf for a large-scale project. Given all-in operating costs of around $10/mcf—and at current Asian LNG pricing of roughly $15/mcf—that yields a margin of $5/mcf, and a six-year payback on investment.

While not a bad investment proposition, Nathan notes that small-scale projects may deliver similar margins at an installed cost of about $15/mcf. Not only does that drop the payback period to three-ish years, but Nathan thinks it will also speed time to production. He estimates that small-scale projects could take as little as two years to go from investment decision to output—whereas large-scale projects could take as many as five years to build.

Chris pointed out though, that fixed costs might be a killer for small-scale projects. Small projects still need a lot of big infrastructure. And they’ll have to complete with larger projects for labor—driving up costs for this key input.

Moreover, Chris noted that cost of capital is likely to be higher for small, less-established developers. He recalled his investment banking experience with a micro-cap group trying to shop Canadian LNG contracts to Asian buyers—noting that getting taken seriously as a tiny company is almost impossible in this space.

Both speakers agreed that permitting and regulatory concerns are one of the biggest risks to LNG projects large or small in BC. More certainty is needed on issues like taxes and the development of needed pipeline infrastructure.

But there was no dispute that the stepping stones for LNG are being laid in western Canada. That means that billions will be spent—even if no projects ultimately get built.

A great thanks to Wolverton Securities, one of the most venerable securities firms in western Canada, for sponsoring a great day.