We all know that solar is a big deal. It is a big industry and it’s going to get bigger.

Solar will see huge growth for the next 30+ years. It is close to inevitable.

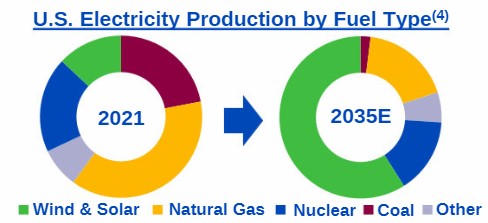

Source: Next Era Energy Investor Presentation

The percentage of the electric grid produced by wind and solar will go from 13% to well over 50% in the next 15 years. By 2050 we could be talking 70%+.

There is big growth coming so there has to be opportunities. Finding the next Enphase (ENPH – NASDAQ) could be a life-changing event (it went from $1 – $330 in 4 years!).

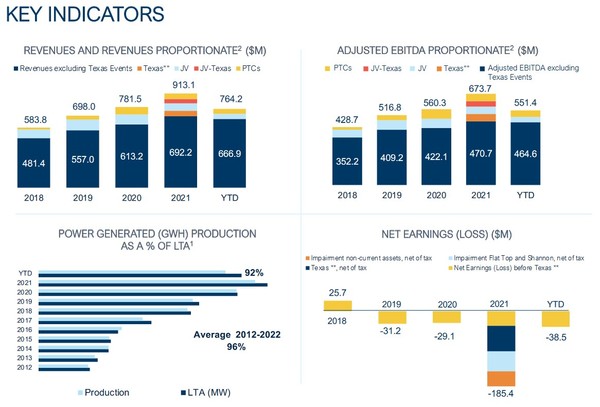

But here’s the thing. Whenever I start looking at the public solar companies my eyes glaze over. I have to look at slides like this:

Source: Innergex Renewables Investor Presentation

Big-time revenue growth. Growing EBITDA with massive margins. Growing dividends. But negative earnings and – much of the time – negative free cash flow.

It is a tough business to wrap your head around. Are these companies profitable or not?

WHAT EXACTLY IS PROFITABILITY?

Solar is generally profitable. Especially with some of the huge government subsidies that are available (such as the investment tax credit in the United States – a credit that offsets about 1/3 to ½ of the upfront capital expenditures of a project!!!).

But! But, but, but. That wedge of profitability is not as big as it looks. It comes with a lot of assumptions. And those assumptions make solar ripe for being distorted – to make something unprofitable look profitable.

I have invested in oil and gas producers for 20+ years. I have watched the cycles ebb and flow. I know (almost) every accounting trick in the oil producer book.

While generating solar is a totally different business than drilling for oil, they are surprisingly similar in a couple ways.

What I will say is this: Just about all the accounting that make oil tricky are in solar as well – AND they are even more severe.

4 BIG POINTS ABOUT SOLAR

The nature of a solar project can be dumbed down to 4 elements:

- Very high upfront cost

- Low operating costs,

- A long payout of consistent cash flows

- Tax rebates that change the picture completely

A solar project is not that much different than an oil well. You build it (which costs a lot of money). You operate it (which costs a little money). And every year you operate it, it generates some cash.

But oil wells have three differences. Each difference makes oil well economics more transparent than solar (I can’t believe I am talking about the relative transparency of oil accounting!).

First, an oil well takes less capex; they cost less. That may seem surprising because oil is a very capital-intensive business.

But solar requires A LOT of capital. A 200 MW solar project may cost $300 million to build. That same project may generate only $20 million to $25 million of revenue a year.

Second, annual operating costs for solar are very small. That same $300 million project may require total annual operating expenses of $7 million. That means solar can look very profitable for a given year – 80%+ gross margins and 70% operating margins.

Third is payback. The payback of an oil well is weighted to the front end because oil wells have a steep decline in production.

This is helpful for an investor because you see the cash come in quickly. It gives some assurance that its not all smoke and mirrors.

For solar, the payback is not as fast. Solar cash flows are generally flat across the length of the asset.

A solar company signs a power purchase agreement (PPA) with a utility or 3rd party off-take. It could be for a flat rate or market rate. It is for the same amount of electricity every year.

The “gives and takes” on revenue are how much the sun shines, how the solar panels efficiency declines over time, and how power prices change. These all have an impact, but not a big impact.

Finally, taxes. Oh my stars, taxes and solar. This is, quite honestly, a whole other article.

The short stack is this: Solar benefits A LOT from tax incentives. Tax incentives can eliminate 30% to 40% of capex off the project completely. For projects as capital intensive as solar is, that is a HUGE win.

Tax incentives are the difference between a solar project being a loss and making a double-digit return.

BE CAREFUL!

This is not easy. It is painful. But it’s the only way.

And it is even harder for a public solar company.

Why? Because public solar companies don’t just operate one project.

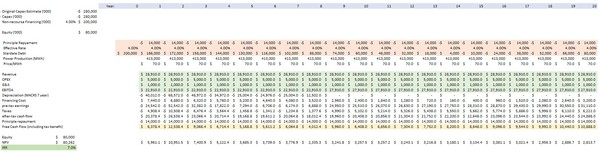

For a single solar project if you do the work and come up with a spreadsheet like the one above you can figure out what that project is worth. You can see what the cash flows have been, what the initial debt was and make sure the debt is being paid back inline with the project life. You can tweak numbers to understand the assumptions. You can’t hide anything.

But because public solar companies are

A. operating multiple projects at various stages of life,

B. aren’t disclosing project level data and

C. are growing, so debt levels are naturally increasing –

…well…you must wade into muddy waters.

My takeaway for solar, as someone who has invested in oil producers, is this: be very careful before investing “for the long run”.

For a trade, considerations about long-run economics don’t matter because the market doesn’t care until it cares. But for the long run, if the assumptions don’t align with reality, eventually that will come out.

There are lots of details that play into that. I tried to give an overview of the main ones in my “4 Big Points”.

I would like to delve into each of these 4 a bit more in an example in another post. You really need an example to see how the numbers work.

But for now, I leave you with this. As I reviewed solar projects in preparation for writing this post, I couldn’t help but be reminded of shale in 2010s.

- Companies focused on operating cash flow and EBITDA because those numbers didn’t reflect the full-cycle costs

- Half-cycle costs that look marvelous

- Large capital expenditures that often exceed operating cash flow

Of course, solar is different in important ways. The biggest being that–the government has solar’s back. They are intent on making sure solar is profitable.

But it is hard to ignore the similarities. Half cycle on solar projects looks great. Companies spew large operating cash flows, and most capex is going toward growth. It looks like a cash generation machine.

Therefore, you see nice dividends for most established solar companies.

But BE CAREFUL. You don’t know the profitability of any given project until you actually build the spreadsheet and work it out from start to finish. And for most public investments, that is simply impossible.

Are the companies drawing on true free cash flow? Or are they just pulling out equity to pay the dividends and levering up (in other words, not paying back the project debt inline with the real depreciation of the project).

Growth is a REALLY good way of making it difficult to figure out what is really going on. That is why some of the biggest scams in the market tend to be growth-by-acquisition companies.

If you are growing fast enough, it can be very hard for the outsider to figure out whether the past investments actually paid off or not.

This is even more the case when the growth is capex-heavy growth and even more-more the case when the payout takes place over a long period of time.

Solar checks ALL those boxes. It doesn’t mean you stay away from it – as I said it is often profitable, especially given the subsidies. But it does mean you need to look at it with a skeptical eye.