It just happened to me–the last of my three kids is out the door and on their own in the world.

This brings mixed emotions for me to be sure.

You spend the first twenty years of their lives trying to get them prepared for this day…..now you pray that they can fend for themselves.

I feel blessed, I couldn’t be prouder of my kids. They will do great.

The behavior of the children of some parents on the other hand is starting to seriously concern me.

The twist here is that the children I’m talking about aren’t human beings.

No, I haven’t been visited by aliens —- the children I’m referring to are actually oil wells that the world is counting on to live up to their parent’s expectations.

And these children have not been performing up to expectations.

Not Exactly A Chip Off The Old Block

In the horizontal oil and gas business, the first well that is drilled on a piece of land or location is considered a parent well. These wells are drilled into the best location and have the entire oil or gas reservoir all to themselves.

The drilling that comes later that drills up the rest of the field, called infill drilling, is referred to as the child wells.

The challenge for horizontal operators is determining exactly how many children each parent well should have and where to place them. The profitability of the entire field depends on getting this right.

Too few child wells leaves a lot of oil in the ground. The producers won’t make that mistake.

But too many child wells crammed into the field causes other problems. Besides overspending, too many child wells incould create fracture interference between the existing producing parent well and the newly fractured infill/child well. (The industry also calls this communication between the wells, and this is one instance where parent-child communication is unwanted.)

Fracture interference is when the hydraulic fractures from one well burst through and into another well. Any fracture interference impacts the production from both the parent and child well.

With the oil industry now getting past the first wave of drilling in all horizontal plays, figuring out how to best manage infill drilling is very important. I believe that managing the child wells correctly is the single biggest issue that will determine the ultimate long-term success of horizontal producers in US shale.

Oil services giant Schlumberger (SLB-NYSE) has been studying the issue and has amassed case studies on a massive number of wells in all the horizontal plays—thousands of wells.

I hate to say it but the initial results don’t look great….

Schlumberger CEO Paal Kibsgaard recently gave an update on what the company has observed at the 2018 Barclays CEO Energy-Power Conference (1).

He focused specifically on what Schlumberger is seeing in both the Eagle Ford and the Permian.

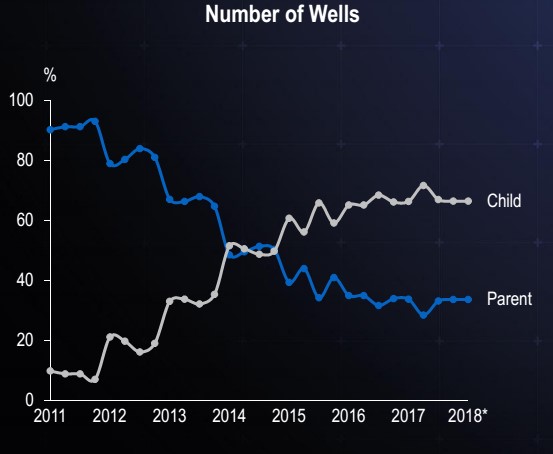

Kibsgaard looked first at the Eagle Ford where child wells went over 50% per year way back in 2015.

That is how a horizontal play goes: the early wells are almost all parent locations. As the play is drilled up there are fewer parents to be drilled and infill/child drilling takes over.

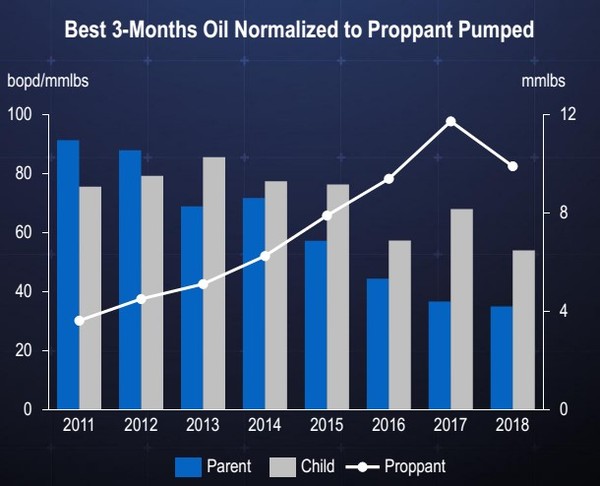

What Schlumberger is seeing is that per dollar spent on drilling and fracturing—the child wells are performing MUCH WORSE than the parent.

In other words, while the child wells might produce more oil because of longer laterals and more proppant—the cost increases for drilling these bigger wells are even greater.

That makes for less profitable wells; child wells have lower returns on capital invested.

The graph below is from Kibsgaard’s presentation. It shows how the amount of production relative to total proppant used has steadily dropped since 2011—close to a 50 percent decline on average.

The percentage of child wells being drilled in the Eagle Ford has already reached 70% and, in the 3-year period since this percentage broke the 50% level, there has been a steady reduction in unit well productivity.

To make up for this, the industry just drills longer and longer wells and pumps higher and higher amounts of sand and water into them.

Production numbers still look great, but it is requiring more and more spending to achieve them.

The Schlumberger CEO believes that the ability to continue to drill longer and inject more seems to be coming to an end, both from a technical and commercial standpoint.

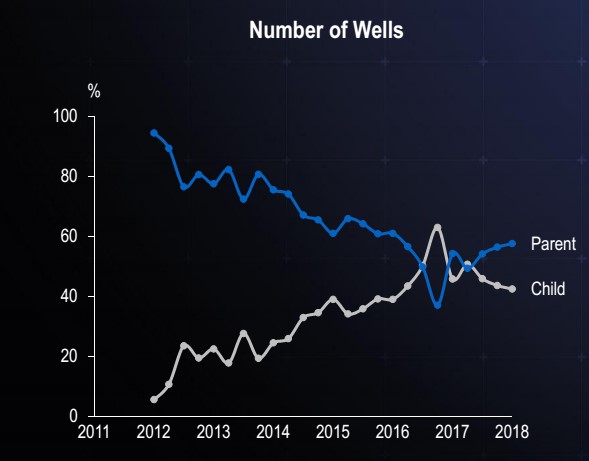

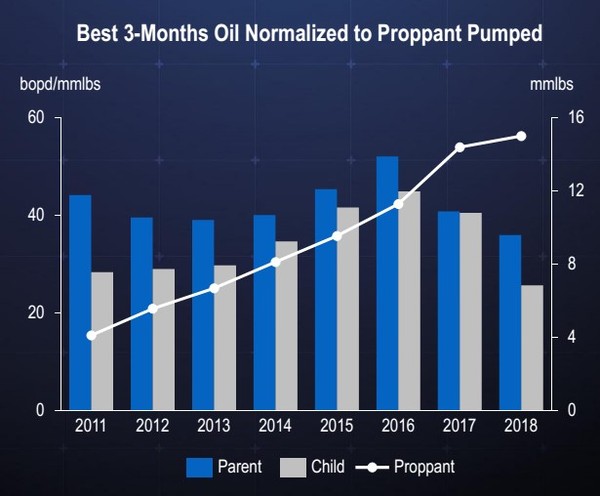

The trend in the Permian looks very similar….just not as far along since the horizontal development here kicked off later.

The percentage of child wells in the Permian is now bouncing around 50% (graph above), and Schlumberger is already starting to see a similar reduction in unit well productivity that has been seen in the Eagle Ford.

Production growth per share, which is makes stocks go up (increasing production but not adding debt or issuing new shares)—is driven by compounded rate of return.

At high rates of return, cash can be recycled quickly and production can grow faster. At lower rates of return companies don’t have as much capital to spend since it takes longer to come back out of the ground.

Schlumberger is strongly suggesting that oil production in the Permian—the oil growth engine of the western world—will slow, now that child wells make up more of production.

Why The World Needs These Children To Shape Up

The parent wells drilled in the U.S. horizontal plays have carried a heavy load for the world in recent years.

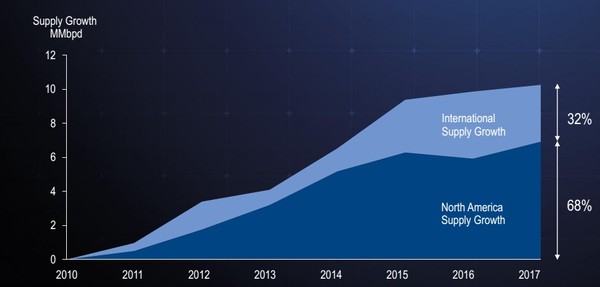

The North American production base, which makes up just 20% of global oil supply—has covered up to 70% of the oil demand growth since 2010. Stop and think about that for a minute. Those are some astounding numbers. There really is very little growth in oil production anywhere outside of the USA and Canada. This was initially the Eagle Ford and Bakken and then the Permian took over.

The consensus thinking today is that the Permian will continue providing 1.5 million barrels per day of annual production growth for the foreseeable future.

It better, because the world is counting on it.

Schlumberger’s Kibsgaard made it clear in his presentation that he thinks that the trend of underperforming child wells should have the market questioning that assumption. He cautions that as the rate of infill drilling increases—this potential (likely?) problem gets bigger.

He also notes that the industry really has no idea how these reservoirs will perform as we continue to inject billions of pounds of proppant and billions of gallons of water into the ground each year.

These are uncharted waters.

These child wells are not destined to always disappoint. The industry is sharing data and continuously learning. Since the year 2000 we have all learned to not bet against the innovative skills of these operators.

If it wasn’t for that innovation we would be staring at $200 per barrel oil today.

At the same time we can’t assume that this problem is going be taken care of.

If these children don’t start filling the shoes of their parents—in terms of economics—there will be a big hole to fill in global oil supply.

EDITORS NOTE: This is all VERY bullish for oil. I am especially bullish on oily US plays–and the Bakken is one of the best. My favourite is a fast-growing $2 stock that is doing so well, management has almost $50 million of their own money in it! They know they’ve got the goods…get my full report on the company BEFORE its next ops update–click HERE .

Keith Schaefer