Investing in Condensate, Part I explained what this hot new commodity is; Part II outlined the bullish case for Canadian condensate demand, and in this third and final article on condensate, I review American efforts to move their glut of condensate north.

Condensate is making uneconomic gas wells profitable for producers in the shale basins of northern BC and Alberta, and creating some great investment opportunities for informed investors.

The reason condensate is king in Canada is that oil sands producers need piles of this light oil to dilute their heavy bitumen for transport, and Canadian production can’t keep up with demand.

How long can this party last? Shale oil and gas basins in the United States are churning out condensate, where demand is very limited. A glut is developing.

That glut is needed up north, so infrastructure players are busy planning, permitting, and building pipelines to move America’s piles of condensate to the Canadian oil sands producers that need it. Once that happens, will condensate’s Canadian price premium evaporate?

It’s an important question, as strong condensate prices are the only leg many Canadian gas producers have to stand on right now.

America’s Unexpected Condensate Wealth

The Shale Revolution has transformed America’s energy scene. After decades of decline, US oil production is again on the rise. The turnaround has been even more dramatic on the natural gas front: shale wealth has transformed the country from an importer to an exporter and pushed prices to historic lows.

Condensate production is an unexpected sideshow of the shale phenomenon – but it is starting to steal some of the limelight because shale wells are producing just so much of it.

Take the Eagle Ford shale basin, which stretches across much of south and east Texas. The basin’s tight sedimentary rocks contain a range of hydrocarbons: wells on the southeastern flank generally produce dry gas, wells in the middle produce gas, natural gas liquids (NGLs), and condensate, and wells to the northwest generate oil and condensate.Eagle Ford producers drilled their wells looking for oil or gas. Condensate was an unexpected bonus – but it now makes up as much as 40% of the hydrocarbons produced from the formation.

Forecasters predict that total Eagle Ford oil output will reach 500,000 to 800,000 barrels per day (bpd) by 2020. A large number of those barrels – somewhere between 250,000 and 400,000 bpd – will be condensate. Compare that to 2011, when condensate production from the formation averaged 130,000 barrels per day.

It means condensate production from Eagle Ford will likely grow by 150% in less than a decade. And Eagle Ford is just one of a slew of shale basins being drilled and fracked apace in the United States to produce oil, natural gas, NGLs, and condensate.

It sounds great, right? Not only are shale basins producing the natural gas and crude oil expected, they are also churning out piles of condensate, a hydrocarbon mixture so light you could often pour it straight into your tractor. Condensate must be making US shale producers happy, right?

Wrong.

Condensate and US Refineries – A Poor Match

Since it is produced alongside oil and since it is in fact oil, producers lump condensate with oil when reporting production volumes. As a result, it seems like US oil production is shooting through the roof. But while domestic output is certainly rising, lumping condensate in with crude is misleading because not every hydrocarbon molecule is created equal – especially through the eyes of a refinery.

Half of America’s refineries lie along the Gulf Coast. With the ability to process 8 million barrels of crude oil every day, this industrial complex truly sets the tone for oil pricing across the country. And guess what? Gulf Coast refineries don’t like condensate.

————————————

What Is This “Freak of Nature” Gas Play?

In short, it has the best economics of any pure gas play I’ve ever seen in my life.

And in this new briefing, I take you through, point by point, why I think this one natural gas stock,

a pure play on gas, could be the single best trade in the sector – junior, intermediate or senior.

Keep reading here to learn more…

————————————-

Refineries are picky beasts, each one only able to process crudes within a particular API range. The Gulf Coast army of refineries used to love light oil, but over the last 25 years the world burned through many of its high-quality deposits of light crude. That forced producers to shift towards heavier and sourer crudes.

In response, US refineries invested billions in upgrades to be able to process these more complicated crudes. In fact, from 2005 to 2009 the US refining industry spent $47.6 billion on heavy oil upgrades.

Then came the Shale Revolution. Fracking technology is the engine for America’s drive for increased energy independence. Suddenly producers were pumping good quality oil from shale basins across the continent.The refineries can handle shale oil. They cannot, however, handle much condensate.

The only way to feed condensate into these medium and heavy oil refineries is to mix the light oil with a heavier crude, to produce a mid-weight blend. But even that is not ideal, because it turns out a mixture of heavy oil and condensate does not produce the same products as a straight crude of similar weight.

Specifically, a mixture of light condensate and heavy crude produces lots of very light products, such as naphtha, and little to none of the heavier and more valuable distillates used to make diesel and jet fuel.

So, since a crude-condensate blend produces less valuable products than a straight crude of the same average weight, refiners discount the price they’re willing to pay for blends.

The unexpected surge in condensate production has collided head-on with low demand from US refineries, resulting in poor pricing. In general, Gulf Coast crude marketers have been paying about $15 per barrel less for condensate than for the light crude it is produced alongside.

Since it is cheaper than crude, refineries are buying some condensate and mixing it with heavier crudes for processing. The products are worth less but input costs are also lower, so it works out ok for refiners’ bottom lines.

It does not, however, work out well for producers. Shale producers invest millions of dollars into each multi-stage frac well. They don’t want to sell half their production at a discount – they want buyers who are willing to pay top dollar for all this light, sweet condensate.

Those buyers, as we learned last week, are north of the 49th parallel.

Getting Condensate to Canada

Canada needs condensate. US producers are flooded with the stuff and want to sell it to Canadian oil sands operators. The challenge is moving it.

The only pipeline currently moving condensate from the US into Canada is Enbridge’s Southern Lights line, which runs from Illinois to Edmonton. It can move 180,000 barrels per day, which can more than handle the 110,000 bpd of condensate being imported now and Enbridge is proposing an expansion.

The hard part, the bottleneck, is getting it to Patoka, where it can enter Southern Lights. Patoka, it turns out, is not particularly close to the biggest condensate-producing shale in the US, which is the Eagle Ford basin in Texas.

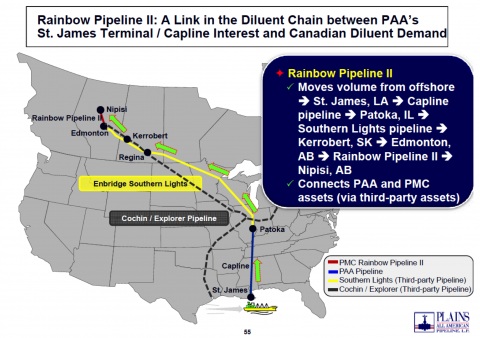

There are ways. For example, Plains All American is using the Louisiana port of St James as a staging post to route Eagle Ford condensate into the Capline pipeline for shipment to Patoka.

Others are using existing gathering networks to move condensate to Corpus Christi on the Texas Gulf Coast, where it is loaded onto barges and transported to St James. Magellan Midstream Partners and Copano Energy are taking this one step further, extending one of Copano’s pipes by 140 miles to Corpus Christi. That line should soon be moving 100,000 barrels of condensate a day.

KINDER MORGAN’S PLANS

Kinder Morgan is also working to establish itself as an Eagle Ford condensate shipper. Kinder is building a condensate pipeline that can move 300,000 bpd from the shale basin to the Houston area, which is already being used to capacity.From Houston, the condensate from Kinder’s line moves through the company’s Explorer pipeline to Hammond, Illinois.

That’s progress, but Canada is still hundreds of kilometers away. To connect its system to Canada, Kinder has two plans:

1. Extend Explorer to connect with Enbridge’s Southern Lights—one ends and another starts in Illinois. That link should be in service by early 2014.

2. The other is to connect Explorer to the Cochin pipeline. Cochin moves propane 1,900 miles west to east—from Alberta to Ontario—through the US, crossing the border in North Dakota and skirting south of the Great Lakes before re-entering Canada in Windsor.

Propane volumes have been declining, so Kinder is proposing to reverse and expand part of Cochin—from east to west—to move 95,000 bpd of condensate from Illinois to Alberta.

Industry support for the project is clear: when Kinder held an open season on its Cochin proposal, the company received binding commitments for 105% of the proposed capacity. US regulators approved the plan in October; Kinder is now awaiting word from Canadian regulators. If all goes according to plan, the reversed Cochin will start moving condensate from the Midwest into Canada by mid-2014.

Plans from Kinder and Plains All American alone will increase Eagle Ford condensate capacity to Alberta by 170,000 bpd by the middle of 2014. Other pipeline projects are also in the works. Not willing to wait, some US producers moving their condensate to Canada by rail.

The upgrades are coming, and all signs indicate that every condensate pipe in the works will be filled to the brim almost from day one. Even without much dedicated infrastructure, condensate sales from the US to Canada have skyrocketed in recent years. Every estimate is different, but some analysts estimate that US condensate exports to Canada have grown 1,000% in the last two years alone.

CONCLUSION

Condensate capacity from the US to Canada should increase dramatically—but it is over a year away. Oil and gas marketers in Alberta tell me oilsands production is rising fast enough to use a lot more condensate—but only time will tell if the market stays in balance, over-supplied, or under-supplied.

There’s a lot riding on this equation for Canadian natural gas producers—strong condensate pricing is the only thing between a lot of them and bankruptcy.

– Keith