By Dave Forest

In Part I of this series we saw how Mexican demand for U.S. gas exports has surged by 92% over the last 5 years. And with proposed new export projects slated to take up to 10% of U.S. production, Mexico could be the surprise driver of marginal demand—and gas prices.

Part II: Who is Poised to Benefit from the “Mexico Explosion”?

But this Mexican export boom does have some intrigue—complete with hastily formed shell companies and mysterious partners—that could become a risk to this mega-trend about to happen…I’ll get to those in a moment.

But first, where exactly will supply for growing Mexican exports—up to 7 Bcf/d based on current projections—come from?

The answer, in short, is the Eagle Ford.

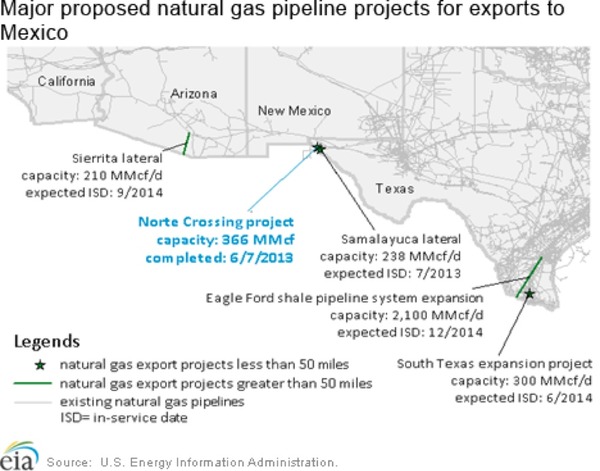

The chart below shows gas exports from the 14 U.S. exit points that serve Mexican markets. There are a few export points in California and Arizona, but the majority are in Texas.

.jpg?__nocache__=1)

There are three geographic clusters of exit points in Texas—in the west near El Paso, the southwest near Rio Bravo, and the south near Roma. Of these, the southern export terminals—shown in purple—have by far seen the largest growth in Mexican exports over the last few years.

Exports from south Texas exit points have grown by 600%, or 240 Bcf/year, since 2009. At the same time, exports from all other U.S. exit points have increased by only 15%, or 43.5 Bcf/year.

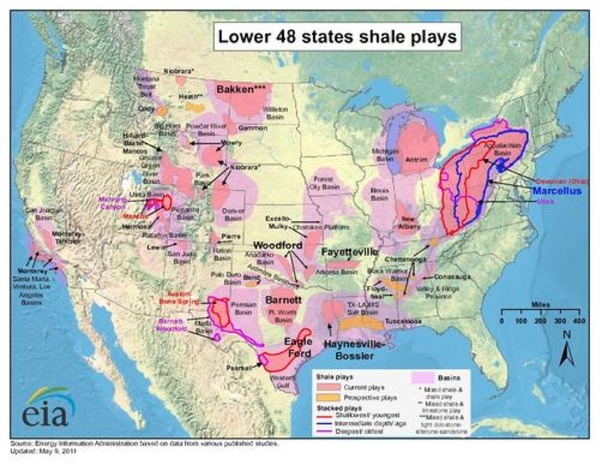

The south Texas exits draw gas mainly from the Eagle Ford shale play, the southernmost of all the major shale gas basins in America.

The Eagle Ford is also an obvious choice to supply more gas to Mexico. The play is seeing some of the fastest production growth amongst U.S. shale basins. (The only other basin that’s growing at the same pace is the Marcellus. But that play is located in exactly the wrong place—the northeast States—to provide Mexican feed.

South Texas and the Eagle Ford also benefit from infrastructure on the Mexican side. Pemex pipelines here are some of the only ones in northern Mexico that currently have excess transport capacity. Other pipelines across the border from Arizona and California are more than 90% full.

For all these reasons, planned export expansion projects are mostly aimed at south Texas. Of the 3.3 Bcf/d in expansion capacity currently planned or being built, 2.4 Bcf/d—about 75%—is centered on south Texas exit points. And Eagle Ford gas.

Another 0.6 Bcf/d in increased capacity is planned for west Texas. Gas for these projects will likely be supplied by the Permian Basin.

Does this mean producers in the Permian and Eagle Ford are a screaming buy? In theory, increased exports should be good for most southern U.S. producers. The gas grid is pretty well connected between producing centers. So increasing prices spurred by growing Mexican demand should transfer across the region.

That said, price dislocations do happen—when gas can’t move fast enough to a high-demand region. This is part of the reason why gas prices in the northeastern States averaged 42% higher than Henry Hub in 2012.

If gas shipping does bottleneck as Mexican exports grow, near-at-hand producers in the Eagle Ford and Permian could find themselves best positioned to reap higher prices.

Gas-weighted Eagle Ford producers include Energy Transfer Partners (ETP-NYSE), DCP Midstream Partners, L.P. (DPM-NYSE), NuStar Energy, L.P. (NS-NYSE), Southcross Energy Partners, L.P. (SXE-NYSE), Pioneer (PXD-NYSE) and EOG Resources (EOG-NYSE).

But Wait a Minute…

All of the above is a big plus for the U.S. gas market—and particularly for producers near Mexico. Assuming it goes as planned.

There are however, a few possible wrinkles that investors should keep an eye on.

The good news is that demand for increased exports looks to be strong. At the “Wilcox Lateral” expansion project in Arizona, operator El Paso Natural Gas has already pre-sold its increased pipeline capacity to two Mexican consumers. Other export projects are also getting “reservation” deals, with Mexican buyers paying up front to reserve gas output from the beefed-up pipelines.

So what could go wrong?

The biggest obstacles are regulatory. So far, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission has been pretty good about moving export expansion projects smoothly through permitting. But other groups in the U.S. may be setting up to make the process more difficult.

Power generators, for one. In early June, Calpine Energy Services—the subsidiary of gas-fired power operator Calpine Corp that secures fuel supplies for the company’s plants—filed a Motion to Intervene in the permitting of the Eagle Ford export expansion project in south Texas.

In the motion, Calpine cites concerns that the company’s “terms and conditions for natural gas service… may be affected.” No other details are given, but it’s a safe bet the company is concerned about increased Mexican exports driving up prices of its currently-cheap natural gas supply.

This could be the set-up for a battle between gas exporters and domestic consumers. The former looking for higher prices, the latter trying to keep natgas more affordable. You can bet those old axes “national interest” and “domestic security” are going to get trotted out.

Mysterious Partners

Calpine has likely chosen the Eagle Ford project because it’s by far the largest export expansion on the books. But the project also has a few other oddities that make it notable.

The project operator is NET Midstream, a major player in pipeline infrastructure for the Eagle Ford shale.

However, when NET applied for its export expansion in May 2013, it didn’t submit the application directly from head office. Instead, it created a new subsidiary—NET Mexico Pipeline Partners—to make the submission.

Here’s the really strange part: NET formed the subsidiary just three days prior to submitting the application. Why such haste to create a new vehicle for a project that must have been in planning for months or even years?

The application document gives a clue. Buried in the boilerplate text is this brief note:

“NET Mexico’s ownership is expected to change in the near future to reflect the addition of a new minority equity member, MGI Enterprises USA, LLC (“MGI Enterprises”). MGI Enterprises is a newly-formed indirect subsidiary of Pemex Gas y Petroquímica Básica, a Decentralized Public Organism of the United Mexican States (“Pemex Gas”). Pemex Gas is a subsidiary of Petroleos Mexicanos, the Mexican state-owned petroleum company (“Pemex”).”

It thus appears that NET is intent on bringing in state-controlled Pemex as part-owner of the Eagle Ford export facilities.

Digging deeper into the filing, it seems the ownership juggling is being done—perhaps hastily—so NET can avoid time-consuming permitting. The application notes that Pemex will “use its existing Department of Energy/Office of Fossil Energy blanket authorization to export the natural gas.”

If Pemex becomes an owner and uses its existing export authorization to get gas out of the country, it saves the American owners a lot of hassle. Right now, NET Midstream is not an international exporter. If they shouldered the project alone, they would need to apply for their own export authorization. An onerous process.

All of this makes sense from a business point of view. But it will be interesting to see how regulators take it if a foreign, government-controlled firm tries to buy ownership in U.S. pipeline infrastructure.

These issues could delay or even de-rail the massive Eagle Ford expansion. Given that this project accounts for nearly two-thirds of planned new export capacity, it’s critical to watch proceedings here. The fate of the “Mexican export boom” may hinge on it.

– By Dave Forest, Contributing Editor