Investors don’t need to hire Sherlock Holmes to help them see what it did to the balance sheet of Cenovus (CVE-NYSE/TSX) after spending $17.7 billion to buy most of Conoco-Phillips (COP-NYSE) Canadian assets this week.

It’s a whopper of a deal.

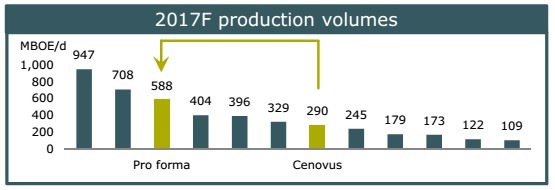

In total what is being acquired adds 298,000 BOE/day of production for Cenovus.

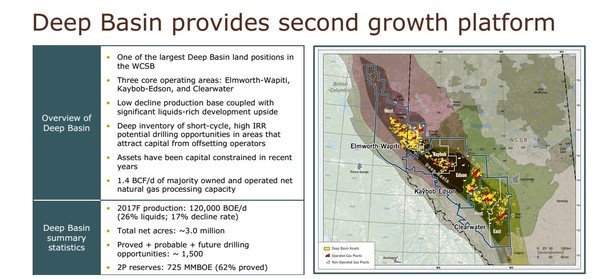

178,000 BOE/day of that relates to Foster Creek and Christina Lake (FCCL) oil sands production (CVE already owns the other 50% of those assets) and the other 120,000 gas weighted BOE/day is from the Deep Basin. There is also 1.4 bcf/d of natgas infrastructure.

The production addition almost exactly doubles Cenovus production to 588,000 BOE/day.

Source: Cenovus Presentation

Here is how Cenovus will cover the $17.7 billion price tag:

- $3.6 billion of Cenovus shares issued to ConocoPhillips

- $3.0 billion bought deal financing

- $11.1 billion through debt and eventually asset sales

It is that last number that has raised more than a few eyebrows.

At the end of 2016 Cenovus was carrying $2.5 billion of net debt—about 0.9 times debt-to-cash-flow (D:CF) on 2017 strip pricing. That put Cenovus at the head of its peer group in terms of balance sheet quality.

With the balance sheet being required fund $11.1 of this ConocoPhillips transaction the net debt figure for Cenovus is going to jump to $13.6 billion.

The transaction has doubled production, but increased debt levels fivefold, and tripled D:CF. Those are not a wash.

From the analyst reports that I have read debt to cash flow levels post transaction jump to more than 3 times from 0.9 times before.

That takes Cenovus from the best in class in terms of balance sheet quality to near the worst of the bunch. It also puts the company in a position where it is much less able to withstand the uncertainties of this business.

That is a lot of added risk. What then is the reward?

According to Cenovus itself the cash flow from the $17.7 billion of acquired assets is running at $1.8 billion per year. That would mean that Cenovus just paid $17.7 billion / $1.8 billion = 9.8 times cash flow for those assets.

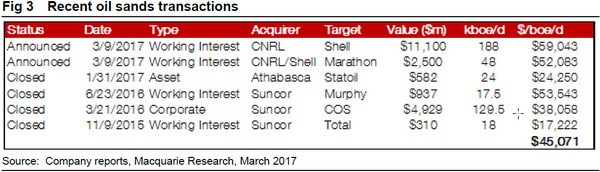

On a flowing barrel basis the purchase metric is $59,000 per flowing barrel.

Neither of those metrics seem like a bargain given what we know about transaction prices in this industry. I’d say that it seems like about a fair price.

At best.

My opinion (and I doubt I’m alone) is that if you are going to do this kind of damage to your balance sheet then you had better be paying a price that is an absolute steal.

I think that on the surface that is clearly not the case here.

When I dig a little deeper I’m even more skeptical.

Earlier this month Canadian Natural Resources (CNQ:TSX/NYSE) paid $58,402 per flowing boe (barrel of oil equivalent; this is how the industry transforms natural gas economics into oil-speak at a ratio of 6:1) for Shell (RDS.A-NYSE)’s oil sands assets.

I don’t like what that implies about what Cenovus just paid for Conoco’s Deep Basin assets.

Follow my logic:

Total Cenovus purchase price – $17.7 billion

Allocate to oil sands based on CNQ deal – 178,000 boe x $58,402 = $10.4 billion

Remainder then allocated to Deep Basin assets – $17.7 billion – $10.4 billion = $7.3 billion.

Source: Cenovus Presentation

If I assume that the FCCL assets that Cenovus bought are worth the same on a flowing barrel basis as what CNQ bought (which is a stretch) it means that Cenovus is paying $7.3 billion for 120,000 boe/day ($60,833 per flowing barrel) of Deep Basin assets.

These Deep Basin assets have only a 26 percent liquids weighting—it’s mostly dry gas, and that is a very steep price for gas weighted assets.

And it may be worse than that.

I’ve used the multiple paid by CNQ to value the oil sands assets that Cenovus just acquired but that is likely too optimistic. The CNQ-acquired production is already upgraded and therefore sells for a higher price than the production Cenovus bought.

My contacts in the oilpatch say the difference between the two deals is this: CNQ captain Murray Edwards waits for deals. Shell came to him. Cenovus had been talking to COP for well over a year, and offered to buy the Deep Basin assets to sweeten the deal and get it done.

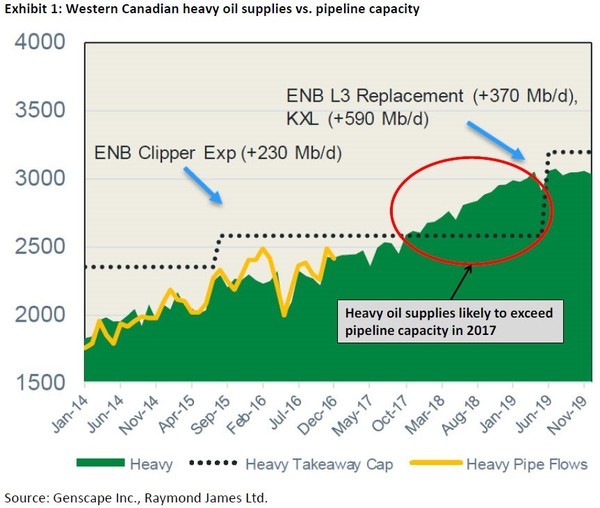

And what about that Western Canadian natural gas glut? Tell me that these Deep Basin assets aren’t going to be faced some very weak natural gas prices in the years to come.

That is another risk on top of the balance sheet risk assumed.

The deal also makes Cenovus less integrated with more direct exposure to heavy oil pricing differentials. With heavy oil production appearing set to overwhelm existing pipeline capacity in 2017 that is another potential negative to this deal.

When you leverage up your balance sheet you aren’t looking to also increase the volatility of your cash generating ability.

Another negative is that a clause in the deal involves contingency payments to Conoco Phillips if oil prices do rise. These contingencies will cause Cenovus to lose 15 to 20 percent of any rise in the price of oil.

With the risks that Cenovus is adding I sure hate to see the company not all of that upside as potential reward.

And speaking of taking away upside from CVE shareholders—COP was emphatic in saying they are selling ALL their 200 million + CVE shares once the six month hold period expires—“in an orderly fashion”. Between the TSX and NYSE, the company trades about 3.5 million shares a day. If they can sell 1 million shares a day—which would impact markets—that’s almost a year of selling. In a flat oil environment—under $55/b—this stock will stay under pressure until The Street can take out that block.

You Don’t Drop $17 Billion Without Giving It Some Thought

It is easy for me to armchair quarterback this transaction.

I really like top quality balance sheets in commodity producers, so I’m pre-disposed to being negative here. And The Street values the optionality of a strong balance sheet. High debt companies always trade at a lower valuation.

So what then is the other side of this?

Why did the Cenovus Board and management team decide to dramatically worsen the company’s financial strength to double the size of the company?

I see a few positives.

First, the plan is to sell assets this year to get the debt down. The company is already marketing both its Pelican Lake and Suffield properties. Selling those will help bring debt levels down closer to 2 times EBITDA. That’s still more than twice where it was pre-transaction but better.

Of course, now everybody else KNOWS that Cenovus wants to sell, so CVE’s negotiating position has been weakened.

Second, I do appreciate the fact that the Deep Basin assets that are being acquired are short-cycle in nature. The existing opportunities that Cenovus has—oilsands—require a long lead time which is not so appealing in this post-crash volatile oil price world.

This gives the company more option to see investments made turn into cash flow much faster.

Third, these Deep Basin assets provide a huge free option on continued technological advancements from the oil industry.

Cenovus is acquiring 3 million acres of land and who knows what that could turn into in the years to come as different formations are exploited.

Fourth, CVE is the partner on the oilsands assets COP is selling—so there is obvious synergies.

Fifth—historically, American companies have to come to Canada at the top of the market and left at the bottom. Ask Mike Rose of Tourmaline.

Sixth–heavy oil and natgas pricing have been stronger this winter than I would have expected. It is possible to say markets for both those products in the US are structurally tighter this year than last (at least, right this second).

The bottom line is now, however, that Cenovus is much more vulnerable to a sustained downturn in the price of oil. It becomes a much more levered play…and I’m not convinced institutional investors want to own that much risk in their Big Positions in oil.

Good balance sheets allow companies to have more control over their long-term success or failure no matter what commodity prices do. Leveraged balance sheets take away a lot of that control. CVE has a lot less control now.

Cenovus has made its bet. Now it is up to those commodity prices to see how it turns out.